Tory Landslide,

Progressives Split

A Datapraxis Analysis of the

UK General Election

Contents

Introduction

3

Analysing the Battlegrounds

7

The regions and nations: what happened where

7

Swings and Roundabouts

9

Bellwether Seats

10

Bolsover

10

Bassetlaw

11

Hendon

12

Finchley and Golders Green

13

Rhondda

14

Sedgefield

15

Stroud

16

Dynamics Behind the Landslide

17

Voter Tribe Analysis: how the British electorate has fragmented

17

How did the Conservative landslide happen?

21

Groups who decided the 2019 election: switchers,

undecideds and the cross-pressured

23

Labour Leave voters

23

Conservative Remainers

24

2017 Labour voters who switched to Remain parties

25

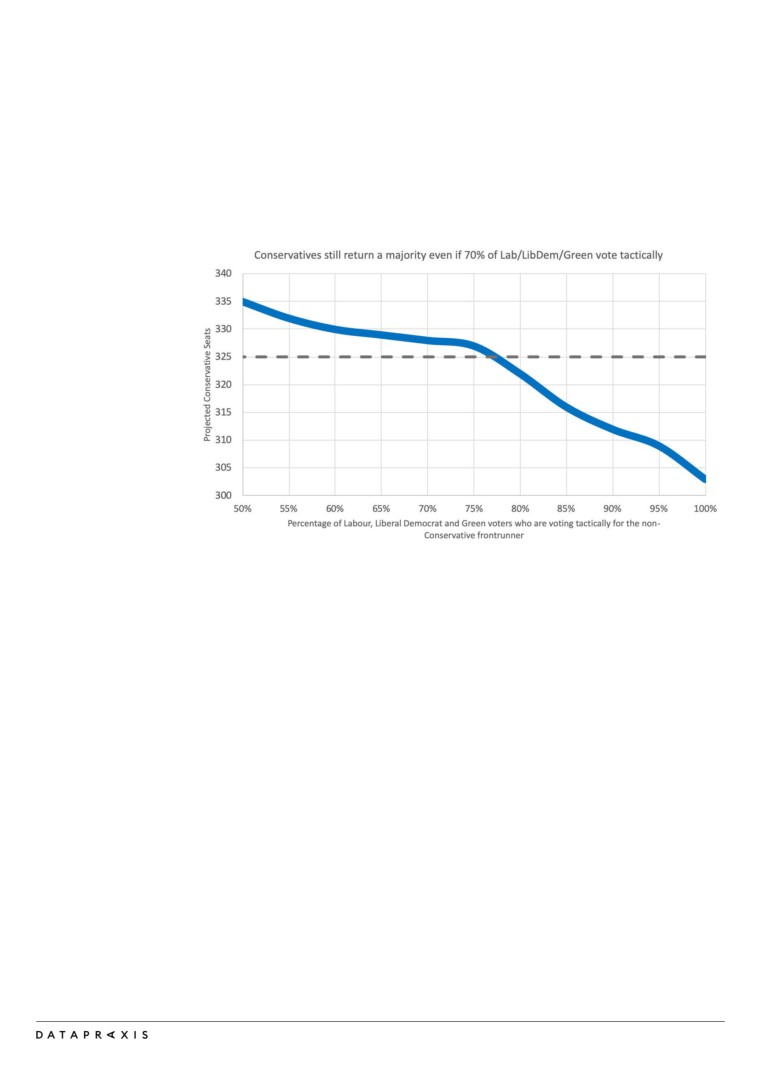

Tactical voting helps, but it is not enough

25

Where could tactical voting have made the most difference?

27

The Undecideds Election?

28

Turnout & voter registration

28

“Get Brexit Done” and Other Campaign Messages

30

Background Notes

32

About Us

Methodology

2

1

Introduction

This election was decisively lost by Labour. Progressives were painfully divided;

all the centre and left-wing parties in England and Wales performed badly, and

Remain campaigners failed to achieve their goals. The Liberal Democrats began

the campaign with immense aspirations, but ended it with one seat fewer. Their

leader, Jo Swinson, even lost her own seat to the Scottish National Party, which

surged to 48 seats, and will push hard for a second independence referendum.

There was no real groundswell of support for Boris Johnson and his Conservative

party. They improved their share of the vote by less than 2% overall, losing over

a million Remainers but gaining more Leave voters. The decisive factor was their

success in winning over voters from the Brexit Party, who decided to stand down

in all seats held by the Tories.

A few hundred thousand more of these voters seem to have switched on polling

day to vote tactically for the Conservatives, helping carry them over the line in a

greater number of tight marginals. This late tactical switch by Brexit Party

supporters is, in our view, the main reason why all the MRP models using the

multi-level regression and post-stratification approach under-estimated the scale

of the Conservative majority.

The Datapraxis MRP model published in the final week was marginally the most

accurate of all the MRPs published in the final week before polling day. It was

94.5% accurate and only mispredicted 35 seats; it was therefore arguably more

accurate than the exit poll, which was 93% accurate and got 44 seats wrong,

despite having fresh election-day data to work with. We worked closely with our

partners at YouGov, using over half a million responses from people giving their

views and feelings about the election, the parties, the campaigns and the leaders.

This was used to give us, and our clients, deeper insight into how people were

going to cast their votes.

YouGov’s final published MRP, released two days before the election, factored in

a Labour surge in the last week and a lower number of seats for the

Conservatives. However, YouGov’s private analysis on the day before the

election, released after polls closed by Professor Ben Lauderdale, picked up a

swing back to the Conservatives, and was significantly closer to the final result.

Labour under Jeremy Corbyn lost nearly 8% of their vote share from 2017,

resulting in the lowest number of seats the party has won in over 80 years (since

1935). Three factors combined to make these results a nightmare for Labour:

1.

Around a quarter of its Leave-supporting voters in the old heartlands -

the so-called “Red Wall” - transferred their vote to the Conservatives;

we estimate the number at 700,000-800,000 voters, based on hundreds of

thousands of polling responses and the YouGov public MRP. Hundreds of

thousands more may have stayed at home, although we need to wait for

more definitive evidence on this point.

3

2.

But crucially, a larger number of Labour’s 2017 voters seem to have

switched to other Remain parties. We estimate that over 1.1 million

Remainers who voted for Labour in 2017 switched to the Liberal Democrats,

the Greens or the SNP in 2019. Importantly, 200-250,000 of the 2017 Labour

Leavers also seem to have switched to these parties, whether because of

“Bregret” or concerns about the Labour leadership or manifesto.

3.

All of these switcher groups had very negative opinions of Jeremy Corbyn.

Both Datapraxis research and other studies find that this is the most

significant factor in Labour’s decline; an Opinium post-election poll found

that lack of trust in Corbyn’s leadership was the main factor, followed a long

way behind by the Brexit balancing act and questions about the party’s

economic policies. The circa 300,000 Remainers who voted Labour in 2017

but switched to the Conservatives illustrate this vividly; our voter tribe

analysis suggests that these people are first and foremost Corbyn skeptics.

In our private polling, Datapraxis asked tens of thousands of people to say in

their own words what their thoughts were about the parties, their leaders and

campaigns. Boris Johnson and the Conservative party were described over and

over again by voters up and down the country using five words: “best of a bad

bunch.” This was true across all ages and loyalties, male and female, young and

old, Leavers and Remainers.

“I was a Labour voter, as was my parents and their parents before, but while

Jeremy Corbyn is leader of the Labour party I will not vote Labour, he has

betrayed the people who were mostly Labour who voted to leave Europe.”

74 year old woman from Darlington in the North East (voting Conservative;

voted Labour in 2015, Labour in 2017 and Brexit Party in the European elections)

“Corbyn is tone-deaf to what he must do. I’ve lost respect for him and how

he weasels out of making any commitment. He needs to ...take a firm LEAVE

or REMAIN position on Brexit. I’ve lost all faith in him and he will be the

reason I do not vote Labour.”

57 year old man from Vauxhall in London (voting Liberal Democrat; voted Remain,

and voted Labour in 2017)

“Boris is an arrogant self-serving individual. Sadly, though, his party has

the best economic record and will do better than Labour at taking the

country forward.”

45 year old woman from Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk (voting Conservative,

voted Remain in 2016)

4

Tactical voting and campaigning played a bigger role than ever before in this election.

But tactical voting by Brexit supporters, the “unilateral pact” through which the Brexit

Party stood down in every seat held by the Conservatives, and the “astroturf” (fake

grassroots) Facebook campaigns which flanked and reinforced the official

Conservative effort, were much more successful than equivalent efforts by

progressives.

The Tories’ majority of 80 seats could have been reduced by 16 if Labour had

properly defended eight of the tighter Red Wall marginals from the beginning, and

by a further 20 or so if progressive tactical voting had been more efficient. Closing

the remaining gap would have required the correction of more fundamental

strategic flaws on the progressive side. But this instant report has no space for a

full lessons learnt analysis; that will come later.

Independent campaigns by Momentum, Hope Not Hate, the Real Change Lab and

Best For Britain could call on decent resources. Some of the most strategic

progressive outrider campaigns were impactful but underfunded. The unions

punched well below their weight, hamstrung by the failure of Labour headquarters

to share its strategic analysis or data. The “Unite To Remain” electoral pact

between the Liberal Democrats, the Greens and Plaid Cymru, set up by

ex-Conservative Remainer Heidi Allen and run by Peter Dunphy, former Treasurer

of the Liberal Democrats, failed completely, and in some marginals - such as

Stroud and Kensington - ended up contributing to the loss of Labour Remain MPs.

According to our analysis in this report, around 78% of voters for the second and

third-placed progressive parties in each seat would have had to vote tactically

instead to block a Conservative majority. This bar is so high as to be unrealistic.

British progressives need to look long and hard at the consequences of their

divisions and bickering over the last decade. A dose of realism is required. It may

be time to think the unthinkable: either the centre and the left can somehow be

reunited under a single banner, or better cooperation and alignment is required

among a diverse flotilla of progressive parties and movements.

One bright point is that 220 women have been elected to the House of Commons:

for the first time ever, more than a third of MPs are women, including a majority of

the Labour and Liberal Democrat contingents (and the only Green, Caroline

Lucas). The new Parliament is also the most ethnically diverse ever.

The Conservatives’ landslide victory will hold for five years. But it is fragile. The

2024 general election could see a dramatic reversal in fortunes. Neither a hard

Brexit nor a long transition period is likely to be good for the country. Boris

Johnson and his allies may come to regret the games they have played between

2016 and now. The voter coalition assembled by Dominic Cummings’s Get Brexit

Done message is temporary and fragile.

5

Britain will be out of the EU by February 2020. The focus of the national

conversation could then turn to the more fundamental challenges dividing our

society and undermining our economy and global environment. Many of the voters

who backed the Tories this year are left-wing on economics, and will end up

disappointed by Cummings’s corporatist turbo-capitalism.

The festering sores of Brexit and immigration which divided these older, heartland

working-class voters from younger, urban and socially liberal progressives will be

settled soon. But there remains a grave risk that the UK will become ever more

deeply riven by the culture wars we see spreading globally, from the US to Austria,

from Israel to India and from Brazil to Poland. Everywhere we look, progressives

are splitting and conservatives uniting. The lessons should be clear. Divided we

fall. But politics is more volatile than ever. Time to shoot the rapids together.

Party

Seats won in 2017

Seats won in 2019

Conservatives

317

365

Labour

262

202

Liberal Democrats

12

11

Scottish National Party

35

48

Plaid Cymru

4

4

Green Party

1

1

Speaker

1

1

Northern Irish parties

18

18

6

2

Analysing the Battlegrounds

The regions and nations: what happened where

This election marked a watershed for Labour. Many of its historic base, traditional

older working-class voters in the Midlands, the North, Wales and coastal towns,

simply could not bring themselves to vote for it. According to Datapraxis estimates,

based on the final YouGov private MRP on 11 December 2019, 900,000 to 1 million

of Labour’s 2017 Leave voters will have ended up backing Boris Johnson or the

Brexit Party.

But a larger number of Labour’s voters - over 1.3 million according to our numbers

- switched to other Remain parties. Importantly, many Labour switchers to other

Remain parties live in majority Leave seats. This group include 200,000-250,000

who voted Leave in 2016; and Labour’s 2017 voter coalition in those places was

often fairly evenly split between Remainers and Leavers. The “ecological fallacy”

has led less thoughtful commentators to assume that all 2017 Labour voters in

majority Leave seats voted for Brexit. But this was absolutely not the case, even if

much of the Conservative and Brexit Party support in these seats comes from older,

formerly-Labour voters who left the party between 2005 and 2017.

Our private polling moved during the campaign, but it showed Labour retaining

sometimes as few as 50% and never as many as two-thirds of people who voted

for Labour in 2017 and Leave in 2016. The final YouGov number was 60% staying

with Labour, 24% going to the Conservatives, just 6% to the Brexit Party and 8% to

other Remain parties. With turnout down across many of these heartlands and

many of these voters remaining undecided until polling day, our research and

analysis suggests that post-election surveys may show that hundreds of thousands

of this group simply stayed home.

The YouGov public model also predicted that 5% of the electorate this time would

be composed of people who voted Leave in 2016 but stayed at home in the 2017

elections. This group of almost 3 million people, many of them former UKIP voters

and some people who typically do not vote in general elections, arguably played a

much more significant role in the Conservatives’ success than any shift amongst

Labour Leavers. These disillusioned ultra-Brexiteers were probably the main target

of Dominic Cummings’s “Get Brexit Done” message.

The Conservatives’ vote went up less than 2% overall; importantly, they also lost over

a million of their 2017 voters who had supported Remain according to our numbers.

Around 7 in 10 defecting Tory Remainers went to the Liberal Democrats, but over

250,000 of them switched directly to Labour and a smaller number to the Greens.

In any case, Labour lost votes in every region and nation of Great Britain. It lost

over 13% of its 2017 voter total in the North East, and over 11% in Yorkshire and

The Humber. It lost over 8% of its voters in the Midlands, Wales, Scotland, and in

the North-West and East of England. Its losses were lower, but still substantial in

London and the South.

7

The chart below shows how the share of the parties’ vote in each region changed

between 2017 and 2019:

Change in Vote Share since from 2017 - 2019

Region

Conservative

Labour

Liberal Democrat

East

2.79%

- 8.57%

5.72%

East Midlands

4.83%

- 9.65%

3.62%

London

- 1.59%

- 6.32%

6.52%

North East

4.23%

- 13.1%

2.28%

North West

1.57%

- 8.67%

2.65%

South East

0.26%

- 6.83%

7.87%

Wales

3.37%

- 8.18%

1.51%

West Midlands

5.11%

- 9.56%

3.72%

Yorkshire and the Huber

3.77%

- 11.21%

3.33%

Scotland

- 2.52%

- 8.78%

2.54%

Northern Ireland

0.17%

0%

0%

The Conservatives increased their vote share in every region except London and

Scotland. But these increases were comparatively modest, peaking at just over 5%

in the West Midlands. In the East Midlands and the North East they scored rises of

over 4%; but everywhere else the increase was smaller, particularly in the South

and the North-West.

The Liberal Democrats increased their share of the vote in every region in the

country, even in Scotland, despite the loss of Jo Swinson’s seat. Our research

suggests that much of their surge came at Labour’s expense. The Liberal

Democrats’ largest increase, nearly 8%, came in the South East. In London they

gained over 6%; but while they are now placed second in many more seats, their

overall total of seats fell.

Datapraxis compared the seats Labour lost this time to the constituencies where it

was wiped out in the 1983 election - the last time the party performed anywhere

near this badly. In 1983 Labour held 17 of its Red Wall seats, but suffered greater

losses in Eastern England and the South East.

Today, Labour’s Red Wall stands no more. Many of the great heartlands of

Lancashire, Yorkshire, Nottingham and the North have fallen to the Conservatives.

Only 5 of the 32 most vulnerable seats in the Red Wall that we identified in the

Datapraxis mid-campaign report, 65 Battleground Seats For Labour, are still held

by the party after this election. Many of the seats lost were not even on the

defensive targets list initially.

8

Labour lost seats like Darlington and Bishop Auckland in County Durham,

Dewsbury and Wakefield in West Yorkshire, Dennis Skinner’s Bolsover seat in

Nottinghamshire, Warrington South and Hyndburn in Lancashire. Other seats to

go were Sedgefield in County Durham, once a safe seat for Tony Blair; Redcar,

which Mo Mowlam held; and Blyth Valley in Northumberland.

Even more significantly, Labour lost eight of the 13 seats we identified as easier to

defend in that report, many of them by tiny margins. It lost Bolton North East by

378 votes, having sent activists instead to campaign in the unwinnable Bolton West.

Bury North was lost by 105 votes, High Peak by 590, Gedling by 679 and Delyn

by 865. A properly targeted and run campaign could have retained all these seats.

Meanwhile, the Liberal Democrats, who began the campaign almost neck and neck

with Labour with a claim that Jo Swinson could become prime minister and cancel

Brexit, ended up with one seat fewer. Swinson lost her own seat of East

Dunbartonshire, and her Brexit spokesman Tom Brake lost Carshalton &

Wallington. Only three of their long list of target marginals were won: St Albans,

Richmond Park, and North East Fife.

Swings and Roundabouts

The biggest swings from Labour to Conservative in this election were in Leicester

East, Bassetlaw, Redcar, Rhondda, Mansfield, Dudley North. Not all of these

seats changed hands. In both Dudley and Leicester East there were particular

local circumstances; the other seats were once places were Labour votes were

weighed rather than counted.

Compare this to seats with the biggest loss of votes for Labour in 1983:

Horsham, Wokingham, New Forest, Buckingham, Winchester, Yeovil,

Portsmouth North - all seats in the South or South West.

12 seats changed hands in the North West, 9 each in the West Midlands and

Yorkshire & The Humber, 7 in the North East, and 6 in Wales. Every one of these

seats went from Labour to Conservative.

This election saw the political realignment catalysed by the Brexit referendum

continue. The top 20 majority Leave seats in the 2016 Referendum are now in

Conservative hands. In the 2015 election, Labour held 5 of these. Mansfield and

Walsall North changed hands in the 2017 election; this time they were followed

by Don Valley, Rother Valley and Stoke-on-Trent North.

The seats that registered the highest Remain votes in 2016 have had a different

trajectory. 13 of these were in London; they include Jeremy Corbyn’s own seat of

Islington North. 12 of them were already held by Labour. The 13th, Putney,

became the only new seat won by Labour in this election, despite two-thirds of its

initial priority seats list having been “offensive” seats it hoped to pick up off its

opponents. A further six of the most Remain seats were in Scotland. All, including

Swinson’s East Dunbartonshire, are now held by the SNP.

9

Bellwether Seats

Constituency: BOLSOVER

The Labour party had held this seat since it was created in 1950. Dennis Skinner,

who embraced his nickname as ‘The Beast of Bolsover’, had been its Labour MP

for 49 years. He was a leading light of the left-wing Campaign Group and a

notorious fixture on the benches in the House of Commons. He lost by over five

thousand votes, losing 16% of Labour’s vote share compared to 2017. The

Conservatives saw a 7% increase and the Brexit Party a 9% increase.

“Do you want polite? Politely I think his

policies (Jeremy Corbyn’s) would put this

country into so much debt we’d take eons

to recover.”

66 year old woman from Bolsover in the East Midlands

(voted Conservative in 2019, Labour in 2015 and 2017,

and Brexit Party in the 2019 European elections)

Mark Fletcher

Dennis Skinner

Votes: 21,791

Votes: 16,492

CON GAIN

2016 Referendum Majority Leave Vote:

68%

Estimated proportion of Labour 2017 voters who also voted Leave:

45%1

Demographics

Once a bastion of the Derbyshire coalfield, this seat suffered its share of

troubles in the 1980s and 90s and still has a relatively high proportion of

people in public housing and higher than average levels of child poverty

compared to national averages.

1

These estimates of the proportion of the Labour 2017 vote who voted Leave in the referendum

come from large sample MRP work conducted by Election Data in 2018. Bolsover is one of the

only seats where slightly more Labour 2017 voters had also voted for Leave rather than

Remain; the remainder of its support came from a mostly-younger group of people who had

not voted in the referendum.

10

Constituency: BASSETLAW

The Labour party has held this seat since 1929. The last time a Conservative

member was elected here was 1924. It was once a traditional mining area which

Labour would have considered rock solid. The Conservatives saw a 12%

increase in their vote share and Labour lost 25% of its share, after the anti-

Corbyn Labour incumbent John Mann stood down dramatically. Turnout was

down by 3% compared to 2017.

Brendan Clarke Smith

Keir Morrison

Votes: 28,078

Votes: 14,065

CON GAIN

2016 Referendum Majority Leave Vote:

67%

Estimated proportion of Labour 2017 voters who voted Leave:

45%

Demographics

An older age profile, with more than 60% of voters 50+.

11

Constituency: HENDON

A traditional Conservative-Labour bellwether seat on the periphery of London.

Hendon had a long history of conservative incumbency until 1997 when it returned

a Labour MP for the first time and was held by Labour until 2010 when the

Conservatives regained the seat.

Pinto-Duschinsky saw his support surge through the campaign, but the final result

in Hendon saw him falling just short, likely due to a combination of Labour’s

challenges with Remainers and Jewish voters, and a lack of tactical voting.

Matthew Offord

David

Clareine Enderby

Portia Vincent-Kirby

Pinto-Duschinsky

Votes: 26,878

Votes: 4,628

Votes: 921

CON HELD

Votes: 22,648

2016 Referendum Majority Remain Vote:

63%

Demographics

An increasingly diverse constituency, including the second largest

Jewish population in the UK and a high number of migrants from both

within and beyond Europe.

12

Constituency: FINCHLEY and GOLDERS GREEN

This seat has the largest Jewish population in the country, 28% in the last census.

It was a safe seat for Mrs Thatcher in the 1970s and 1980s, but went Labour in

the 1990s. Luciana Berger, who resigned from the Labour Party over anti-semitism,

stood here for the Liberal Democrats, but failed in the end to unseat the sitting

Conservative MP. Labour lost 20% of its vote share and the Liberal Democrats

added 25%. Even though there was a clear anti-Conservative majority in this seat,

it was completely split, handing victory to the Tories.

Mike Freer

Luciana Berger

Ross Houston

Votes: 24,162

Votes: 17,600

Votes: 13,347

CON HOLD

2016 Referendum Majority Leave Vote:

62%

Demographics

Part of the prosperous outer London ring. 40% of the population have

higher level qualifications, well above the national average, and nearly

40% were born outside the UK.

13

Constituency: RHONDDA

Rhondda is a quintessential Labour seat in the South Wales Valleys. Labour held

on here despite losing nearly 10% of its vote share. This is a seat where they were

helped by the Brexit Party, which split the Brexit vote, taking 12%, while the

Tories added only 6% to their vote share. Many voters also stayed at home this

time; turnout was less than 60%, down over 6% since 2017.

Chris Bryant

Hannah Jarvis

Branwen Cennard

John Watkins

Votes: 16,115

Votes: 4,675

Votes: 4,069

Votes: 3,733

LAB HOLD

2016 Referendum Majority Leave Vote:

55%

Estimated proportion of Labour 2017 voters who voted Leave:

39%

Demographics

Rhondda is one of the most deprived constituencies in the UK. 31% of

its population have no qualifications. People have a lower life expectancy,

and worse health outcomes than the Welsh average. 22% of people

here receive benefits.

14

Constituency: SEDGEFIELD

Sedgefield in Durham has been continuously represented by a Labour MP since

1935. Tony Blair held it from 1983 to 2007. In the past, Labour support in parts of

the constituency was nearly monolithic, but no longer: it now has a Conservative

MP. In this election, Labour lost 17% of its vote share. The Conservatives and the

Brexit Party both increased their share of the vote by 8%.

Paul Howell

Phil Wilson

Votes: 19,609

Votes: 15,906

CON GAIN

2016 Referendum Majority Leave Vote:

57%

Estimated proportion of Labour 2017 voters who voted Leave:

33%

Demographics

Over 27% of the population in Sedgefield have no qualifications; 27%

have no car. One of the main local employers is the Hitachi factory, but

this seat also includes some wealthier suburbs of Darlington.

15

Constituency: STROUD

The Liberal Democrats stood aside here for the Green Party as part of the “Unite

to Remain” electoral pact between these two parties and Plaid Cymru. Labour’s

overall vote share in Stroud dropped by nearly 5%; the Greens’ vote share rose by

just over 5%, and the Tory vote also increased slightly (by 2%). The net result was

the loss of a key Labour-Tory marginal seat, and an increase of 2 in the

Conservative majority. Progressive parties would do well to reflect on the

learnings from this and other similar experiences across the country.

Siobhan Baillie

David Drew

Molly Scott Cato

Votes: 31,582

Votes: 27,742

Votes: 4,954

CON GAIN

2016 Referendum Majority Remain Vote:

55%

Estimated proportion of Labour 2017 voters who voted Remain:

70%

Estimated proportion of Labour 2017 voters who voted Leave:

20%

Demographics

This is a sparsely populated, largely rural Gloucestershire constituency.

It has a highly skilled workforce, reflecting the nature of its high tech

manufacturing and service base. Stroud itself is now becoming a

commuter town for the South East and South West.

16

3

Dynamics Behind the Landslide

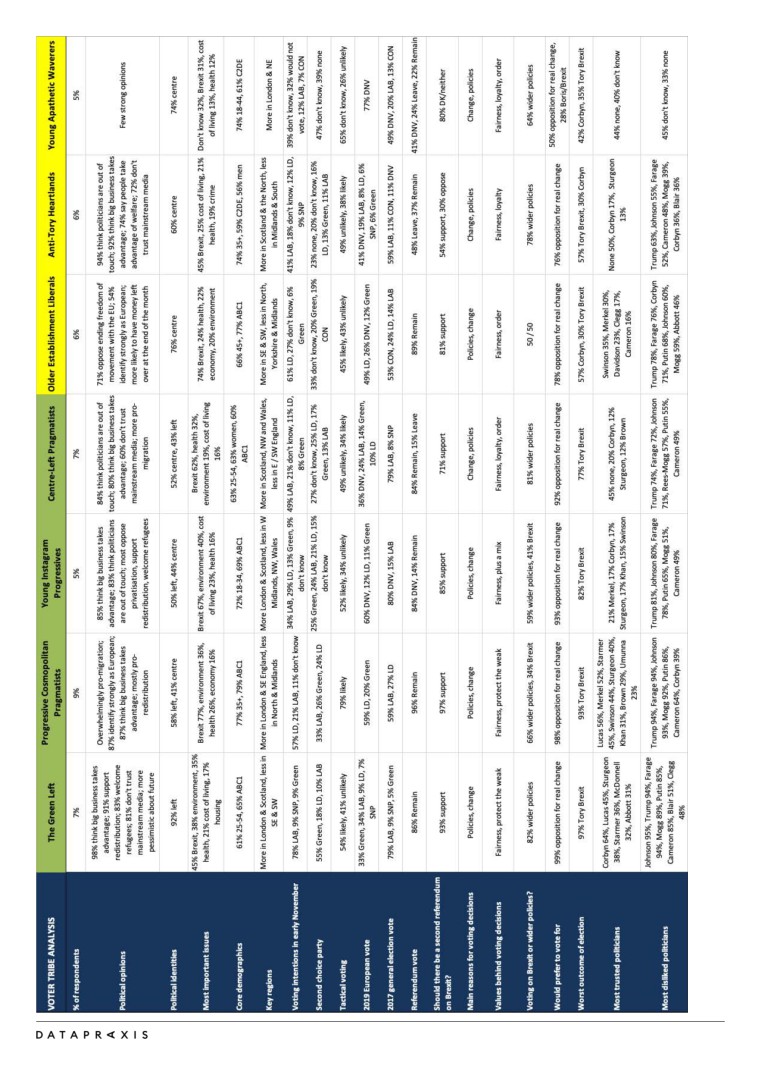

Voter Tribe Analysis: how the British electorate has fragmented

Around the time this election was called, Datapraxis commissioned a 10,000

sample poll from our research partners YouGov, which was fielded between 28th

October and 5th November 2019. We used the responses to build a “voter tribe

analysis” that divides up the electorate into fourteen different groups. A cluster

model assigns respondents to a tribe based on patterns of similarity between their

responses to over 85 questions. This analysis vividly illustrates how worldviews,

value systems and political tendencies differ across the British electorate. This is a

story of multi-dimensional fragmentation; it cannot simply be explained by Remain-

Leave or left-right polarisations.

The first seven tribes we identified lean toward progressive views, and together

make up 45% of the electorate. “The Green Left” is the heart of Jeremy’s Corbyn’s

support base, and “Centre-Left Pragmatists” are the other core Labour-supporting

group. Together with the Green Left, “Progressive Cosmopolitan Pragmatists” and

“Young Instagram Progressives” were the groups most likely to vote tactically

against the Conservatives.

Many “Older Establishment Liberals” voted Conservative under Cameron, and

even in 2017; but they mostly now support the Liberal Democrats. “Anti-Tory

Heartlands” voted more Leave than Remain, but are generally Labour and

supported a People’s Vote. “Young Apathetic Waverers” are less likely to turn out,

and more likely to be swing voters if they do.

“Boris has been shown to repeatedly lie and deceive the public. I have voted

Conservative in every election to this point, but cannot vote this time for

Conservative due to the content of his character. Many people in the country are

struggling and the policies are doing nothing to benefit the poorest in society.”

40 year old man from Bradford East in Yorkshire and The Humber (voting Liberal Democrats in

2019, voted Conservative in 2017 and in the 2019 European Elections, and Remain in 2016)

17

Turning to the remaining 55% of the electorate, five tribes seem to have rallied

heavily behind the right-wing parties in this election. The “Farageist Ultra-

Brexiteers” voted overwhelmingly for the Brexit Party in the European Parliament

elections earlier this year. They started the general election campaign splitting their

votes between Farage’s party and the Conservatives, but most of them ended up

voting tactically for Boris Johnson to ‘get Brexit done’. Meanwhile, “Empire 2.0

Brexiteers” are more typical older Conservative voters, who also voted heavily for

the Brexit Party in the Europeans but have returned to the fold since.

One of the most interesting swing voter tribes are the “Anti-Corbyn Get-It-Done

Switchers”, who voted heavily for Labour in 2017, but overwhelmingly for the

Conservatives in this election. They are fed up of Brexit and want to get it over

with; they intensely dislike the Labour leader. They are more pro-system than most

groups, and also support policies like redistribution. This group likely formed the

core support base for the failed breakaway Independent Group in Parliament,

which later became Change UK; independent ex-LabFour MPs like Ian Austin and

Ivan Lewis also ended up endorsing the Tories in this election.

“I can not bear the thought of Jeremy Corbyn and his stupid ideas running

the country, but Johnson is so bad. For the first time in 59 years I feel afraid

of what will happen to the country and of the dangerous direction it is going

in. There are no real leaders any more no one to be trusted. We need

someone with integrity and honour to lead us, not a cad and a clown.”

59 year woman from Chesterfield in the East Midlands who was planning to vote Conservative,

voted Conservative in 2017 and in the European Elections, voted Remain in the Referendum.

“Older Brexit Swing Voters” split between the Conservatives and Labour in 2017,

then moved more decisively toward the Brexit Party and the Tories. They are an

older, more female tribe, who lean to the left on economics but to the right on

social issues. It seems likely that they turned out heavily for Boris Johnson this

time. “Older Traditional Recalcitrants” are more reticent to give strong views, but

typically lean strongly Conservative. Majorities of both these tribes also dislike the

Labour leader.

“Crazy, cannot afford their proposals, don’t like their team especially Corbyn, do

not respect them for not honouring the Brexit vote which they said they would,

not trustworthy.”

66 year old man from Vale of Clwyd in Wales (voting Conservative; voted Labour in 2015,

Labour in 2017 and Brexit Party in the European elections)

20

“The Older Disillusioned” are a group who typically have not voted recently,

although 2 in 5 of them voted Leave; they are intensely anti-immigration. “The

Younger Disengaged” usually do not turn out and have few strong views -

although they leaned toward supporting opposition parties over Johnson at the

start of the campaign, and a few of them turned out for Labour in 2017.

This voter tribe analysis conducted by Datapraxis at the beginning of the election

campaign helps shed new light on its outcome. In the 20 or so seats the Brexit

Party contested seriously, the Farageists and the Empire Brexiteers split the right-

wing vote, helping Labour to win even on a diminished share. But elsewhere most

hardline Brexit supporters, most of the right and some centre or swing voters all

fell in behind Boris Johnson’s Conservatives, especially after the last-minute Brexit

Party collapse from 2.9% to 2.1%. Remain and progressive voters were much more

widely scattered among Labour, the Liberal Democrats, the Scottish and Welsh

nationalists and the Greens.

Any party or leader seeking to assemble a winning voter coalition in future must

understand the differences (and similarities) of worldview and values amongst

these fourteen tribes. In particular, it is important to understand the lived

experience and worldviews of working-class voters in towns and rural communities

in the former Labour heartlands. Millions of these people voted Remain, as well as

the millions who voted Leave; hundreds of thousands did not vote at all in the

referendum. Taken together, these are the voters most likely to decide the outcome

of the 2024 general election. The battlefield is now very different from what it was

when John Major, Tony Blair, Gordon Brown, Nick Clegg and David Cameron were

vying with each other for the support of the aspirational middle-class, although

that group is now the one more likely to be voting tactically in the South.

How did the Conservative landslide happen?

Labour’s seismic losses to the Conservatives across its traditional heartlands have

been a long time coming. While every community is different, multiple factors have

combined in a perfect storm. They include decades of economic stagnation and

increasingly precarious work; austerity, cuts to local government and the retreat of

the social safety net; the decline of the high street with the rise of offshore internet

commerce platforms; and the departure of children and grandchildren to study and

work elsewhere.

These factors have intersected with an increasingly intense skepticism about a

system many believed to be rigged against them, strong anti-immigration feelings,

a sense that politicians are out of touch, and a belief that social security and public

21

services are being exploited by others. The relentless drumbeat of sensational and

misleading tabloid news stories has been taken to a new level, with the rise of

social media as a vector for disintermediated communications in which “filter

bubble” effects can lead to fake news and sentiment spreading like wildfire.

All these dynamics have been decades in the making. But Brexit crystallised them.

It provided an imaginary path to national renewal and “taking back control”,

splitting these voters off from the Labour Party and bringing them closer to the

Conservatives or the Brexit Party.

These shifts have taken place against a broader backdrop of a generalised decline

of party loyalties. Decades ago the class-party alignment was much clearer,

although there has always been a significant Conservative working-class vote,

including in Thatcher’s time. But in the last two decades, social trends and political

and economic dislocations have led to increasing churn; record numbers have

switched to vote for a different party in the three elections since 2015.

Five years ago, the Scottish independence referendum shook the kaleidoscope in

that former Labour heartland, opening the way for the Scottish National Party to

replace Scottish Labour as a hegemonic force. This development has made it a

great deal harder for Labour to win an overall majority in Westminster, and that

does not look likely to change soon. While it recovered briefly in Scotland in 2017,

it fell back again in this election. There is a real risk that a similarly lasting

de-alignment could now take hold in the traditional heartlands won by the

Conservatives in the Midlands and parts of the North.

Trust in politicians also seems to be declining slowly; the combined net approval

ratings for the two candidates to be Prime Minister at the beginning of this election

were lower than in any previous election. In thirteen of our fourteen voter tribes, large

majorities agree with the statement that “Politicians are out of touch with the interests

of people like me” (the exception is the Young Apathetic Waverers, who say they don’t

know). There is only one tribe where a majority agrees that “I can trust the government

of the UK to look after my interests” - the Anti-Corbyn Get-It-Done Switchers.

Our research across Europe has found related patterns of system-skepticism and

fragmentation in most countries, although they vary by degree and in specifics.

The state of public opinion in France, Italy and Eastern Europe is particularly

volatile at present.

In proportional electoral systems we see a trend toward political fragmentation and

coalition government. But in the UK, the first past the post system still

disproportionately favours whichever party is best able to concentrate a large

22

minority bloc behind it. This has mostly been the Conservatives in recent decades,

with the exception of the 1997-2010 period.

In the 2019 general election, the Liberal Democrats spent much of their time

attacking Labour rather than the Conservatives. Animosities reign between Labour

and the Lib Dems over many issues, in particular Brexit, the austerity record of the

2010-2015 coalition government, and who is best-placed to win each seat. In

short, fragmentation is hurting progressives and helping conservatives win.

Groups who decided the 2019 election:

switchers, undecideds and the cross-pressured

Labour Leave voters

In this election, almost one in four Labour Leave voters crossed the rubicon and

voted Tory for the first time, according to private MRP research now published by

our partners at YouGov, which was based in private polling also licensed to

Datapraxis2. Depending on turnout, we estimate that Labour Leave to Tory

switchers were between 700,000 and 800,000 voters. Labour in the end retained

only 60% of its 2017 Labour Leave vote; earlier in the campaign, it was doing even

worse among this group.

Nigel Farage made a great noise about targeting Labour Leave voters in the

heartlands. But in the end, the Brexit Party was winning at most 6% of this group

according to the MRP. Remarkably, Lauderdale and Blumenau estimate that a

larger number - fully 8% of the 2017 Labour Leavers, more than 200,000 people -

switched instead to Remain parties (the Liberal Democrats, the Greens or the

SNP). According to our review of open-ended polling responses, the key drivers of

this shift are likely to be either that they have changed their mind about Brexit, or

that they do not like Labour’s current leadership.

Brexit is best seen as a symptom, not a cause, and certainly not the only cause of

Labour’s loss of its Leave voters. This move was decades in the making, and there

was no single factor. The widespread media attacks on Jeremy Corbyn over his

alleged unpatriotism, anti-semitism, pacifism and radical left views resonated

powerfully in many of these communities. Most of these voters are also older; the

Tories won the overwhelming majority of over 65s in this election.

2

“MRP Methodology, Tables and Figures”, Ben Lauderdale & Jack Blumenau (YouGov), 11

23

“Untrustworthy. Sold his long-held political beliefs to stay party leader. I was

a Labour member, since Labour’s stance and betrayal of democracy I’m not.

I’ve also cancelled my union membership.”

60 year old man from Wolverhampton in North East, West Midlands (voting Conservative; voted

Leave in 2016, Labour in 2017 and Brexit Party in the European elections)

Datapraxis’s partners at Election Data have created a classification of five types of

Labour Leave voters: blue-collar working households, legacy older council estate,

those struggling to make ends meet, the totally disaffected, and a younger group

termed transient terraces.

Taken collectively, 52% of Labour Leave voters disliked Jeremy Corbyn according

to our massive-sample polling. A similar proportion - 48% - disliked Boris

Johnson. They were evenly split on whether a Tory Brexit or a Corbyn led

government was the more serious danger to the country.

Interestingly, 54% of Labour Leave voters listed the NHS in their top two issues,

compared to only 37% for whom Brexit was in their top two issues.

Conservative Remainers

These voters are mostly well-educated and in secure, well-paid employment. A

common thread for Conservative Remain voters is that they have agency over their

lives. They have traditionally prioritised economic stability and prudence and

“small-c” Conservatism and are turned off by the divisive rhetoric of the right of the

Conservative party.

Our partners at Election Data have created a classification of five types of

Conservative remain voter. These include older, successful voters in sought after

areas, older voters in commuter belts and outer suburbs; middle income families;

young families in new housing, and couples or singles in their first home.

Unsurprisingly, 88% of this group dislike Jeremy Corbyn; 33% like Boris Johnson.

66% stated that the most serious danger to the country would be a Corbyn-led

government, compared to only 10% saying they were more worried about a

Tory Brexit.

“Boris is an arrogant self serving individual. Sadly, though, his party has

the best economic record and will do better than Labour at taking the

Country forward”

45 year old woman from Bury St Edmunds in the East of England (voting Conservative, voted

remain in 2016 and did not vote in the European elections in 2019)

24

2017 Labour voters who switched to Remain parties

As noted above, we estimate that over 200,000 2017 Labour Leave voters switched

to the Liberal Democrats, the Greens or the SNP. They can be added to over 1.1

million 2017 Labour Remain voters who switched to Remain parties (mostly the

Liberal Democrats), according to Datapraxis’s estimates based in the published

YouGov MRP numbers from 11 December 2019.

In total, we therefore estimate that over 1.3 million of Labour’s 2017 voters

switched to other Remain parties, while something like 700,000 to 800,000 of its

Leave voters and 300,000 of its Remain voters switched to the Conservatives (the

latter group most likely because of their views on the leadership).

This was despite the policy of supporting a second referendum to give the people

the final say on Brexit, which the Labour leadership arrived at late and reluctantly.

Without that shift, we can confidently say that Labour would have lost many more

of its majority of Remain voters in this general election; it might even have fallen

well behind the Liberal Democrats going into this election, and have been wiped

out much more badly. The previous policy of delivering a “Red Brexit” was even

less viable than the Final Say position.

Switchers from Labour to other Remain parties are generally prosperous.

Compared to labour voters, climate change weighs heavily on their mind; 30%

listed it as one of their top two most important issues.

Similarly to the Labour Leave voters, 52% of this group dislike Jeremy Corbyn.

They were deeply opposed to Brexit; only 1% agreed that we should “Get Brexit

Done, unleash Britain’s potential.” It is important to note, however, that only 5% of

this group believed that a Corbyn led government posed the greatest danger to the

country, compared to the 69% who believed that a Tory Brexit was the greater

threat. This is perhaps ironic. In some seats, if they had stuck with Labour, they

might have made the difference.

Tactical voting helps, but it is not enough

Datapraxis ran a model on the election results to see what would have happened

with various levels of tactical voting by Labour, Liberal Democrat and Green voters

in England and Wales. We found that even in the unrealistic scenario where all of

these people voted as a block for the frontrunner party best placed to challenge

Conservatives in each seat (for example, if all Liberal Democrats and Greens had

voted Labour in places like Kensington, and all Labour or Green supporters had

voted Liberal Democrat in places like Esher and Walton), this would only just avoid

a majority Conservative government.

25

The results would then have been as follows: 303 seats for the Conservatives, 241

seats for Labour, 28 seats for the Liberal Democrats, 52 seats for the SNP, 4 for

Plaid Cymru, 1 for the Greens, 3 seats for others and 18 Northern Irish seats.

Only a full “progressive alliance” or electoral pact in which parties agreed to stand

down for each other could have delivered this outcome, and even then it might have

been in jeopardy if some of the supposed tactical voters abstained. If the smaller

parties in each seat are on the ballot, they will inevitably attract some votes. We

found that around 78% of voters for non-frontrunner progressive parties in each

seat would have had to vote tactically to block a Conservative majority this time.

Tactical voting and “squeeze” dynamics in which voters opt for the party best

placed to stop the party they like least clearly played a significant role in the final

outcome. According to reports from the main tactical voting websites, perhaps 20%

of voters checked a tactical voting website, and they are likely to have been

disproportionately concentrated in 100-150 key marginal seats.

In 2019, the five seats in which Labour suffered its highest loss of vote share were

as follows:

— In Southern England, Esher and Walton (where it lost 77% of its 2017 vote),

Mole Valley (down 63%), and St Albans (down 62%) - all losing mostly to the

Liberal Democrats.

— In Scotland, Angus (down 64%), Stirling (down 63%) and Falkirk (down 62%).

A plurality of Labour’s lost votes here have most likely gone to the Scottish

National Party according to our data - either on an anti-Tory tactical vote, or

for other reasons. The remainder were likely driven in large measure by

unionist tactical voting, splitting more to the Conservatives than the Liberal

Democrats, as the Tories successfully positioned themselves as the leading

unionist party in many seats.

26

Where could tactical voting have made the most difference?

Datapraxis have identified 10 seats where systematic anti-Tory tactical voting could

have changed the outcomes, reducing the Conservative majority by 20. In six of

these seats - Kensington, Wimbledon, Carshalton & Wallington, Chipping Barnet,

South Cambridgeshire and Cheadle - it was very close indeed.

Constituency

Conservative %

Labour %

Liberal Democrat %

Wimbledon

38.4%

23.7%

37.2%

Kensington

38.3%

38.0%

21.3%

Cities of London and

39.9%

27.2%

30.7%

Westminster

Finchley and

43.8%

24.2%

31.9%

Golders Green

Carshalton and

42.4%

12.4%

41.1%

Wallington

Chipping Barnet

44.7%

42.6%

10.3%

South Cambridgeshire

46.3%

11.7%

42.0%

Watford

45.5%

37.9%

16.1%

Cheadle

46.0%

12.3%

41.8%

Truro and Falmouth

46.0%

38.3%

12.1%

Particularly in Kensington and Wimbledon, contradictory recommendations from

different tactical voting websites may have helped put the Tory candidate over the

top. The GetVoting website published by Best For Britain at the beginning of the

campaign was based on old polling data and recommended the Liberal Democrats

in far too many seats, including Putney, Truro & Falmouth, Camborne & Redruth

and Filton & Bradley Stoke. They later corrected this error and updated their model.

Remain tactical voting sites like the People’s Vote and Remain United ignored

constituency polling published in the Evening Standard and the final YouGov MRP

for Kensington to back ex-Conservative Liberal Democrat Sam Gyimah there. They

were operating on the hypothesis that Tory Remainers would be more likely to

switch to him, but he fell well short. Tactical.vote’s methodology of using primarily

2017 election results was accurate in many places, but wrong in Finchley & Golders

Green, Cities of London and Westminster, and Wimbledon.

27

The Undecideds Election?

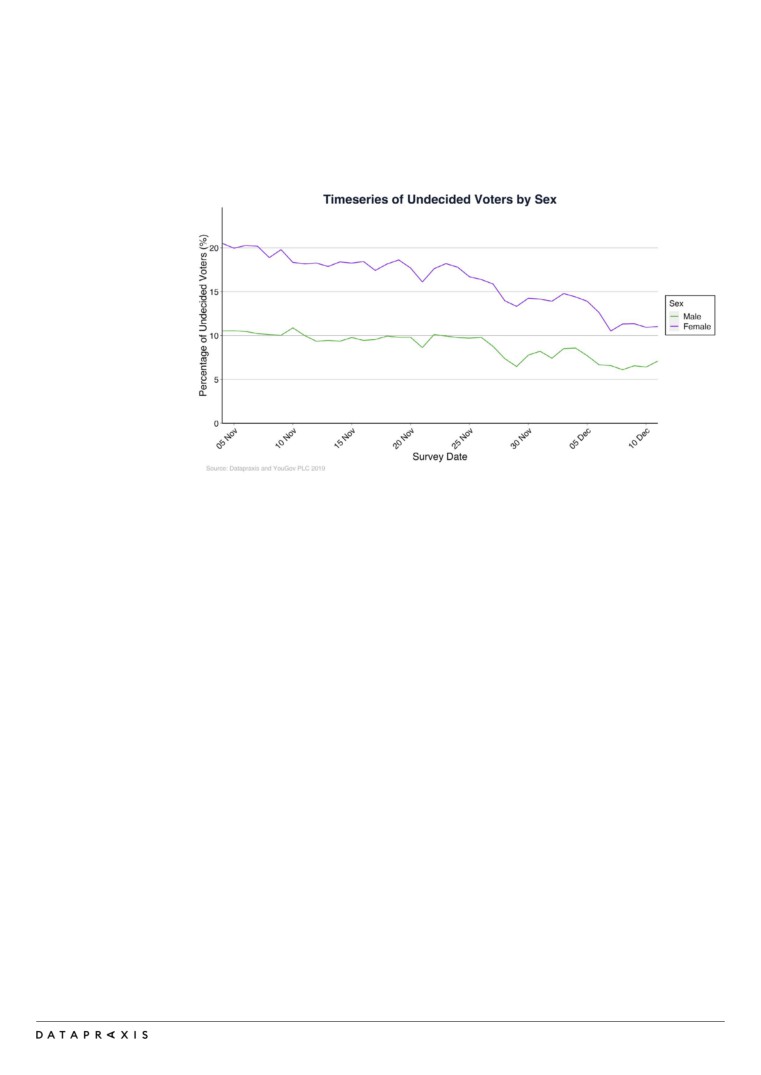

A remarkably high number of voters were undecided during the course of this

election, particularly women, although by 11th December the figure was similar to

that on 7 June 2017. This chart shows the trend lines and the difference between

men and women; almost twice as many female voters were undecided at the

beginning of the campaign.

People were undecided for many different reasons. But according to our research,

three major factors were as follows:

-

Many of them did not like either of the main candidates to be Prime Minister;

–

Many of them were cross-pressured by their Brexit opinion diverging from the

position of the party they usually vote for;

-

Many others were unsure either whether to vote tactically, or which party was

best placed to beat the party they liked least.

Turnout & voter registration

Over 3.2 million people registered to vote during the general election campaign,

two thirds of them under 35. This was a significant increase on the 2.3 million who

registered in the 2017 campaign, and a testament to the impressive work of non-

partisan registration campaigns like Vote For Your Future. Datapraxis modelled the

split of new registrations versus re-registrations, and the expected voting intention

of the newly registered voters, for every seat in which we were working with

clients. Many campaigns did not request or receive updated voter rolls after the

registration deadline.

28

The biggest increases in turnout between 2017 and 2019 took place in the following

seats (excluding Buckingham, where the former Speaker John Bercow stood down):

+7%Angus, Leeds North West, Putney, Cities of London &

Westminster, Battersea

+6% Kensington, North East Fife, Chelsea & Fulham

+5% Esher & Walton

The biggest drops in turnout (excluding Chorley, the seat of the new Speaker

Lindsay Hoyle) were as follows:

Stoke-On-Trent North

-19%

Wolverhampton South East, Luton South

-12%

Brentwood & Ongar, Kingston Upon Hull East & Hessle,

-11%

North Antrim, Slough

Across the Red Wall of formerly Labour heartland seats, overall turnout was

slightly down. Our best hypothesis is that some of the Labour Leave vote stayed

home in the end; almost half of the undecideds in this group found it very hard to

choose who to vote for, even when pressed with a squeeze question about a two

horse race toward the end of the campaign.

29

4

“Get Brexit Done” and other Campaign Messages

Datapraxis works with our campaign clients to analyse, develop and test

emotionally resonant messages. We tested hundreds of messages during the 2019

UK general election campaign or in the run-up. This gave us and our clients a

comprehensive map of the most important drivers of opinion and voting decisions

among different voter groups and tribes.

Dominic Cummings’s “Get Brexit Done” was an extraordinarily effective campaign

message for this election. While arguably not as game-changing as “Take Back

Control”, we found it resonating with a large majority of the public at large, and

with the overwhelming majority of all parts of the voter coalition the Tories needed

to assemble - even many Conservative and Labour Remainers. The British public

are simply sick of the Brexit tug-of-war, and want to move on to other pressing

issues. The irony is, of course, that Brexit is far from over and done with. We will

see whether this ends up damaging Johnson in the months and years to come.

The Conservatives’ attack lines were also highly effective. The “cost of Corbyn”

attacks (“The cost of Corbyn will hit you in the pocket”) cut through well, as did

the lines that “the country can’t afford the promises in Labour’s manifesto”,

and that “a hung Parliament just means more dither and delay”.

Labour had many lines in this campaign. Their initial headline message, “It’s Time

For Real Change”, tested brilliantly. It communicated the radicalism of the

manifesto positively, connected with the strong desires for change across all voter

tribes, and made clear the contrast with the Tories’ offer of “more of the same”.

However, it was used too infrequently and inconsistently in the campaign.

Headquarters started using “On Your Side” instead after they belatedly realised

the threat to the Labour Leave group; but this message was too inert to be an

effective counter to “Get Brexit Done”.

What proved much more successful for Labour was the counter-attack on the

NHS. Rather than bland familiar messages about Labour being “the party of the

NHS” or saving the NHS, the specific threat of US-style privatisation of the health

service from a post-Brexit Trump trade deal was communicated vividly and

relentlessly, through leaked documents, viral videos and a swarm of movement

communications.

The core values statement that “Our NHS is not for sale” was so powerful that

Boris Johnson started trying to reclaim it. But “Boris Johnson will sell our NHS

to Donald Trump” and similar messages gained very broad and rapid agreement,

as did “you can’t trust the Tories with the NHS” and “I’m worried my local

hospital can’t cope”.

This attack effectively disrupted the Brexit-Boris-NHS nexus of associations

created through the “We send £350 million a week to the EU, let’s spend it on

our NHS instead” message repeated relentlessly by Vote Leave in the 2016

30

referendum. We believe the NHS attack line was a major factor in Labour’s

resurgence of support among its 2017 Leave voters and other key groups. Our

private polling found the NHS rose in importance through the campaign, becoming

a bigger issue even than Brexit among undecided voters.

But it was all too little, too late. Negative messages about Jeremy Corbyn proved

overwhelmingly strong, in particular among Labour Leave and Conservative

Remain voters. Regardless of the origins of these negative perceptions, and

despite the party’s position strengthening through a strong campaign and massive

grassroots mobilisation, this was the fatal factor in the end for Labour’s prospects

in this election. While statements like “We need a new government to deliver real

change” had a slight edge over “We need to re-elect the current government to

get Brexit done”, more people were more worried about Jeremy Corbyn as prime

minister than about a Boris Johnson majority and a hard Tory Brexit.

The Liberal Democrat message that “Jo Swinson could be the next prime minister”

was one of the worst performing messages we have tested anywhere in Europe.

“Britain deserves better than Boris Johnson or Jeremy Corbyn” tested much

better; but a weak, shallow and hubristic Liberal Democrat campaign failed to get

anywhere near closing that deal with the social liberal and soft Conservative swing

voters they were targeting.

In the end, “best of a bad bunch I suppose” is the message which perhaps best

summarises the common sense of 44% of the British public. This is no ringing

endorsement. We see choppy waters ahead for Boris Johnson’s Conservatives.

We hope progressive parties and movements are ready to learn the lessons, to

ask themselves tough questions, and to work hard on message, strategy and

organisation in the coming months and years.

31

Background Notes

About us

Datapraxis provide strategic advice, public opinion research, modelling, analysis

and campaign services to political parties, non-profits, media and research institutes

across Europe. We worked with several campaigns in the 2019 General Election.

Paul Hilder is the founder and CEO of Datapraxis, and a leading authority on new

politics, big data and networked movements. He was previously co-founder of

Crowdpac, openDemocracy and 38 Degrees, and has played leadership roles at

Change.org, Avaaz, Oxfam, Purpose and the Young Foundation. He has twice been

a candidate to be General Secretary of the Labour Party.

Methodology

This report is based on analysis and modelling by Datapraxis as well as our

partners at YouGov. The underlying fieldwork source is almost 600,000 private

polling responses supplied by YouGov between 4th November and 11th December,

with typically 850-950 responses per constituency.

32