On my way home from labour conference 23, I visited the People’s History Museum. It was a bit of a vanity trip as I was looking for any documentation related to NOLS’s adoption of a comprehensive, as in wide ranging, education policy. I was on the NOLS national committee, elected at their 76 conference and was given responsibility for the Education policy portfolio. I found the reference to my election in the Labour Party’s conference report, for 1977. As said, I held the education portfolio for that year and I led the organisation, with much help from the other officers, in developing a comprehensive policy which was presented to conference 77. My being allocated responsibility for education was not necessarily one of choice, since most of us at the time were interested in macroeconomics, industrial and labour relations policy or international solidarity issues, where Chile solidarity and the Anti-Apartheid campaigns loomed large and also what was to become the EU continued to be a live issue from the 75 referendum.

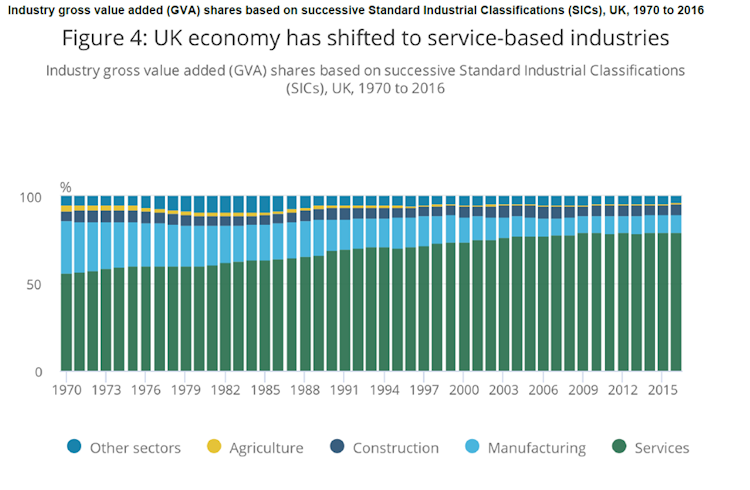

I remember that I was keen to engage with the Labour Government and its great debate on education. It seemed crucial to establish that education should benefit its students and was not just an investment for human capital in what in retrospect could be seen to be a dying economy.

I found a copy of Labour Student dated Spring 78 reporting on that 77 conference, in which my successor, John Merry wrote a review of the new education policy. I summarise from Merry’s article, as I could not find the papers, that the key demands were,

- Education as a right for all, and its purpose is to develop potential of students

- Education must serve all needs, not just business, and education to be democratically managed.

- The ending of discriminatory access; our concern was that the children of the working class had access to Higher Education; at the time 4% of the school leavers went to university and the same number entered the Polys.

Merry, criticised the Labour government plans because the binary higher education system mirrored the class structure, and arguably continued the 11+ split where Universities were designed for non-technical high quality education, and the Polytechnics for technical high quality education and the FE’s for non-high quality education. It took another 25 years to abolish the binary divide, and FE policy remains a problem to this day.

The Blair administration’s 50% university entrance target a has changed the constituency of youth. When browsing the records of the 80s, one of the fascinating things I notice is that how the language was oriented towards young workers. The proportion of young people in higher education was very small, even if one didn’t share the workerism of the Militant, building a mass organisation required such an orientation.

On the question of democratic control, Merry wrote,

We do not believe that education is an industry to be nationalised under workers control but rather is a social service in which workers and present recipients have an important but not complete role to play.

Today I have much more sympathy with elements of the Militant line, at least they tried to find a means where, local workers demands could be ameliorated and shaped by consulting with other workers and the government; Clause IV’s demands on control were possibly developed in contradiction to both, the workerism/faux-soviet demands of the Militant and the student vanguardism of elements of the left who were demanding massive student representation on the governing bodies of the universities and polytechnics. NOLS’s practice at the time was also to permit a minority paper to be presented to the conference.

He also said, “We oppose courses purely aimed at training people to play a subordinate role in a capitalist firm.”. This was probably aimed at the recently founded Manpower Services Commission and its Youth Opportunities Programme.

The conference paper would seem to have focused on Higher and Further education as students, we were attempting to ensure that we reflected the learning from our position in society. We can also see from the changes in the economy and the development of macroeconomic theory that the role of investment in education is much more important than we thought at the time and while there was some cynicism in expanding the target of university entrance numbers, it is/was an important reform as was the more high minded abolition of the binary divide.

We needed Romer, and Mitchell to establish theoretical frameworks where maximising potential is preparing people to participate in the economy. I was ahead of my time but the focus of Labour’s consideration of education policy turned to primary and secondary education with the introduction of national curriculum, academy schools and league tables. I don’t think they helped as they all contributed to the de-professionalisation of teachers and teaching. The lesson I reflect on today is a rule I learnt many years later; the amount of process and measurement doesn’t necessarily bring about good outcomes.