Gordon Brown’s Commission on the constitution of the UK has finished its report. Much of the press focus on the proposal to abolish/reform the House of Lords but it is much more comprehensive than that. I originally wondered if in its way it is as ambitious as the Chilean constitution that failed to win approval in 2022. On reading it fully I conclude that it is not. They do however, propose a new constitution, with entrenched individual rights, of health, education and housing and a duty of the state to ensure no-one is poor. For all their controversy in this country, these rights are commonplace around the world.

Brown introduces his Commission’s report in the Guardian, saying,

… our key insight is that in order to build economic prosperity across the United Kingdom and alleviate fast-rising poverty, political reform is a necessity. Any economic plan will fail unless the right powers are in the right places in the hands of the right people. The goal of an irreversible transfer of wealth, income and opportunity to working families across the United Kingdom is dependent upon the irreversible transfer of political power closer to the people.

As ever, there’s nothing wrong with Brown’s mind or instincts.

I have now read the proposals for reform and made copious notes, and ask myself how useful this is. For those who think that constitutional reform is not relevant to progressive politics, I’d remind them that Blair’s first administration made major changes to the British Constitution, introducing devolution for Scotland & Wales, signing the Good Friday Agreement, re-established city wide government in London, and passing the Human Rights Act and Freedom of Information Act, they also reduced the number of hereditary peers to 92 but failed after two attempts to abolish the unelected Houe of Lords having been accused of like today’s Tories selling peerages.

Richard Murphy, in a blog article with which I basically agree criticises the lack of ambition and principle on both Proportional Representation & the rights of self-determination of the Nations of the UK. Despite this the report is more ambitious than its critics and commentators allow. I have four points to make.

- The problem is parliamentary sovereignty. Any reforms made by Parliament can be undone by Parliament. How do we entrench such reforms including the promises of subsidiarity and social rights? I was quite despondent when I started the report and remain concerned if the only answer is a basic law and judicial review. But, the proposal to reform the House of Lords may be the clever change required. The report recommends the entrenchment and protection of devolved power to be safeguarded by new powers of the reformed second chamber of Parliament. If the renamed/reformed House of Lords has a legal and democratic mandate to veto changes to the new settlement, maybe we can embed this redistribution of power within the United Kingdom or whatever remains of it after the Brexit experiment. I note, however, that by focusing on House of Lords abolition, rather than the reform of Parliament, the Labour Front bench and the media miss the point and allow opposition within the Party and country to grow.

- I believe the proposed powers to be devolved within England lacks ambition, and the continued fetishisation of Directly Elected Mayors is a mistake and a brake on the ability to allow communities to have their say. Blair’s government tried and failed to run a regional policy; I argue it failed because they became diverted by both regional democracy and, shamefully, workfare policies. Brown proposes that the Job Centre network is devolved to [large] local authorities as part of a devolution of a skills investment programmes, despite being silent on FE governance, much of which has been privatised. He talks of devolving powers on trains and buses, housing with respect to planning, licensing landlords and funding retrofitting of insulation and a trivial engagement in cultural investment. The report focuses on devolving supply side programmes, while maintaining the investment powers in a renamed National investment Bank. The report also fails to talk about the loss of EU subsidy for innovation, and to counter regional poverty lost through Brexit, or the opportunities to fund regional development should we rejoin the EU or Horizon Europe. On the question of scrutiny, he sees the London Assembly as a suitable model and makes no mention of the abolition of the independent and feared Audit Commission nor its resurrection. The promise of effective subsidiarity is important and worthwhile, but the report’s reticence on devolving investment programmes and the focus on metropolitan and Mayor led authorities is disappointing and at the end of the day weakens the devolution promise and fails to address the anti-corruption agenda. There is of course no way a commission consisting of Labour local government people are going to criticise the Party’s inability to hold its elected [local] leaders to account.

- The huge gap in the proposal is there is no mechanism to guarantee funding against the time horizons needed for programme management. What time horizon’s they do consider are ludicrously short (3 years). None of this works without bi-partisan or constitutional commitment to local ‘needs-based’ funding with a long-term guarantee. Money must be transferred between geographic areas and guaranteed as it is in Scotland, albeit only by convention. These guarantees need to be protected from parliamentary sovereignty. The whole of these English local government proposals cannot work without a transfer union. “From each according to their ability, to each according to need”.

- There are series of proposals about Westminster. Obviously abolishing the House of Lords is one step, but the commission recognises the need to clean Westminster up1 and recommends, eliminating foreign money from UK Politics, banning MPs second jobs, a new Independent Integrity and Ethics Commission, with the power to investigate breaches of a new, stronger code of conduct, a new body to ensure all appointments in public life are made on merit, juries of ordinary citizens2 to determine whether rules have been broken, a new UK wide anti-corruption Commissioner, appointed by the parliaments of the UK but no suggestion of powers, except to report to Parliament[s]. It’s probably not enough, we need to ask why it doesn’t work today as in principle most of these measures are in place, as law or convention. Our money laundering and anti-corruption laws are amongst the strongest in the world. The problem is the accountability and motivation of the regulators, which brings us back to the Audit Commission, the Police and even the ICO, who have been abolished or seem loathe to investigate leading politicians. For most MP corruption, the House of Commons is its own3 judge and jury and we also have the increasing politicisation of the control process as we see in the US, where people designated as judges, even in treason cases, take the Party whip. I believe the proposal for an independent integrity and ethics commission is just tinkering although I am unsure what else to do.

PR & the Commons, and judicial review

Proportional Representation and the Commons is clearly an issue that causes fear in the leadership layers of the Labour Party that the Commission represented. We know why this is not mentioned. The E;ectoral Reform Society have made a statement, entitled, “Brown Commission reforms offer first blueprint for much needed democratic renewal” has some interesting further reading to explore, they say, albeit in image only, “without addressing the Commons, the aims of Brown’s Commission can only fall short”.

The Institute for Government, in its, much briefer review raised the issue that a basic law i.e. a constitution requires more powerful judicial review and this may have some undesirable side effects. I also ask myself, what if Dr Fritz Sharpf is right, and that judge defined basic laws will stymie social democratic ambitions; remember Thameside and “Fare’s Fair”.

The remainder of this article looks at the proposed size of the new second chamber, and at their proposals for more Civil Service job dispersal.

Is 200 the right number?

I have looked at some of the academic papers on the size of parliaments, and the ratio of elected politicians to people. One interesting point argued is that assemblies that are too small are easily captured (by the executive), and those that are too large, more likely to deliver reduced quality as people look for unnecessary work, “The Devil finds work for idle hands”. One proposal to guide avoiding these threats is that assemblies are sized to be the cube root (∛) of the population. Personally, I am not convinced.

While representation and these ratios, are important, the size of a legislative chamber also needs to take account the amount of effort required to perform its functions. An assembly of over 1,000, will almost certainly mean that some/many representatives will not speak in the chamber, however this metric underestimates the work of committees and individual efforts by representatives to rectify wrongs. The availability of time in the chamber, will be reduced if the chamber has restricted, in terms of dates and hours, sittings times. We should also note the House of Lords has become the initiating source of legislation when the government has a busy programme and plays an important role in scrutinising secondary legislation, which itself should be more limited than currently occurs because the sole purpose of secondary legislation is to avoid effective parliamentary scrutiny.

Another aspect of Britain’s democratic deficit is that we have on the whole far fewer local elected politicians than others in the OECD; it’s one of the outcomes of the increasing centralisation of the British state. The Commission makes no proposals on this, although it’s obvious preference for Executive Mayors and more limited control commission sized scrutiny bodies is clear.

An assembly of two hundred with geographical balance means some very small delegations from the Nations. Having more than one cohort, with each on a different cycle will be difficult while maintaining geographical balance if the chamber is so small.

I believe that on the basis of representation, focus, independence, integrity and effort, 200 is far too small.

Civil Service Reform

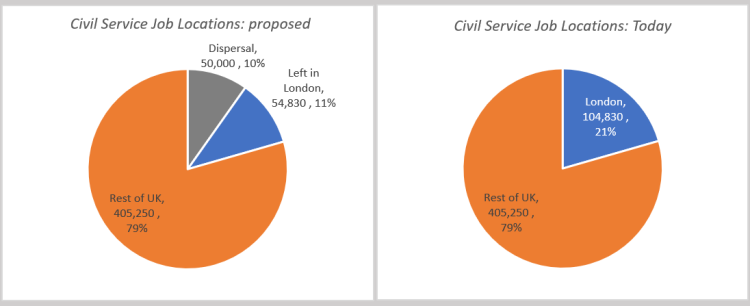

One of the proposals is based on a concern about the state, quality and independence of the civil service, and they propose a legislative solution, but they also propose to relocate 50,000 Civil Servants from London to the Regions, this is fanciful nonsense.

Most Civil Servants are now outside London. Those in London are either in service delivery or close advisors to Ministers.

As of March 2022, there were 510,080 people employed in the home civil service, across the UK and overseas. Of these, 104,830 (21%) were based in London – an increase of almost 3,000 since March 2021 and 13,170 since March 2020.

50,000 from 510K is doable, 50K from 104K when over half of these people are engaged in service delivery to Londoners, i.e. DWP, MoJ & HMRC sounds infeasible to me, particularly given the current government is planning to relocate 15,700 in the next three years. The extensive list presented as targets for relocation, will almost certainly generate a trivial numbers of jobs for relocation’

There is no mention of the downsides of relocation of government departments also known to me as Sheffield syndrome; when the Manpower Services Commission Head Office moved from London to Sheffield in the 80’s, it generated a local house price boom, pricing out long term residents.

See also on my wiki, https://davelevy.info/wiki/new-britain-new-britcon/, my notes,

- and https://davelevy.info/wiki/new-britain-new-britcon/#devolution, on economic devolution in England,

- and https://davelevy.info/wiki/new-britain-new-britcon/#cleaningup on corruption in Westminster

- and https://davelevy.info/wiki/new-britain-new-britcon/#200 on the size of the 2nd chamber

A New Britain: Renewing our Democracy and Rebuilding our Economy on the Labour Party web site also SURL at https://bit.ly/newrules4britain, and my mirror.

[1] It’s a bit ironic that the man you introduced MPs expenses as a means to capping MPs salaries is making these proposals.

[2] US style grand juries?

[3] There is a genuine problem in that MPs privilege was designed to ensure that their constituent’s voice could not be supressed by the Government, a recurring problem we see in the Labour Party where accusation of breaking the rules is enough to silence people within the Party.

Pingback:Devolution – davelevy . info / wiki

Pingback:Labour and Devolution – davelevy.info

Pingback:The popular will of the masses – davelevy.info

Pingback:How to make an EU citizens’ assembly – davelevy . info / wiki

Pingback:Labour’s Programme 2023 – davelevy . info / wiki